Part 1: Defining Value in Healthcare

Value-based care, a term largely attributed to Michael Porter and Elizabeth Teisberg, is the idea of structuring incentives to reward achieving desirable and efficient outcomes, rather than rewarding the delivery of a given service.

This isn’t new. In the last decade, countless programs and companies have been founded around the idea of achieving this sort of value. But we believe it is more critical and achievable than ever: with the continuous rise in the cost of healthcare, policy makers and private sector actors are turning to value-based frameworks more enthusiastically and completely.

At Pearl, we are focused on value-based care to help make our country’s healthcare apparatus sustainable — and to empower physicians and patients to collaborate in a system that delivers excellent care affordably. In this article, we seek to define value as we conceive of it at Pearl.

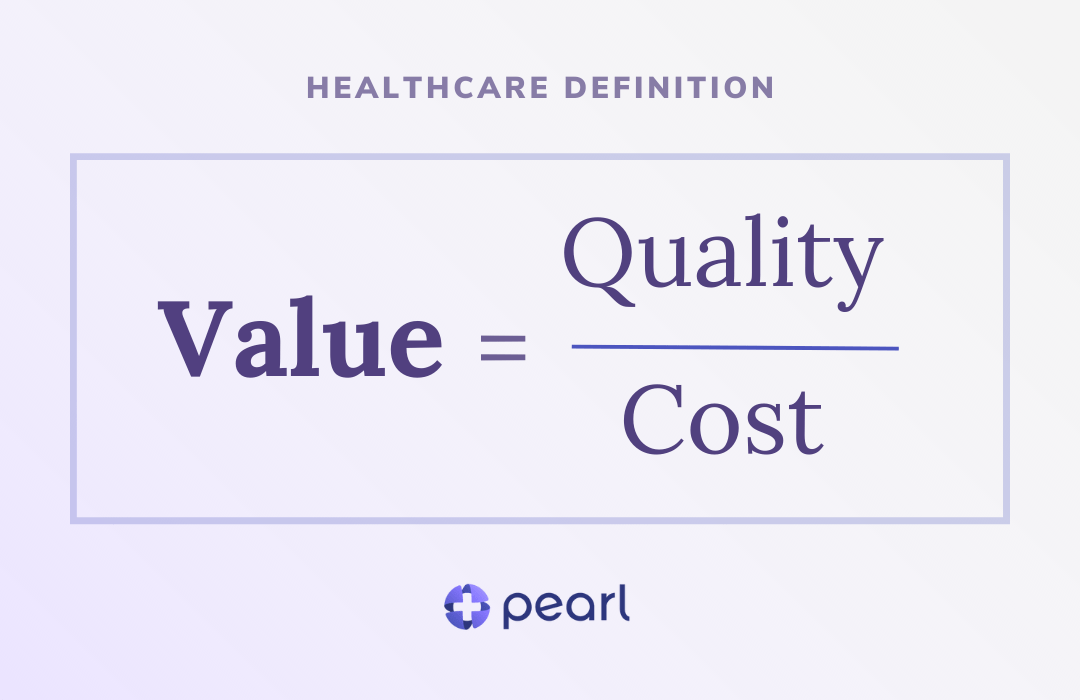

In the context of healthcare, value is often defined as:

This equation clarifies the primary drivers of value and acknowledges that, in general, providers and the entities that support them can achieve better outcomes (i.e., ‘greater value’) through two vectors:

- (a) Raising the quality of healthcare delivered; and

- (b) Reducing the cost associated with providing that care.

Before diving too far into the implications here, let’s get a bit more granular on each.

Optimizing Costs in Healthcare to Drive Value

‘Cost’ is generally broken up into two sub-components:

- Unit Cost (i.e., how much a provider charges for a given service, or unit, of healthcare delivered); and

- Utilization (i.e., how frequently those services are delivered).

As we at Pearl are currently focused on Traditional Medicare, we actually don’t have to worry about the first component: every provider that a patient could see is billing at or below 100% of the Medicare fee schedule, so there isn’t as much variability in unit costs as is commonly experienced in the commercial US healthcare markets.

So that means we are left to focus on utilization. There are two core ways to address utilization:

- Minimize the need for it through prevention; and

- Ensure it is at the ‘right level’ — i.e., not over-treating or over-escalating care provided vs. the needs of the patient.

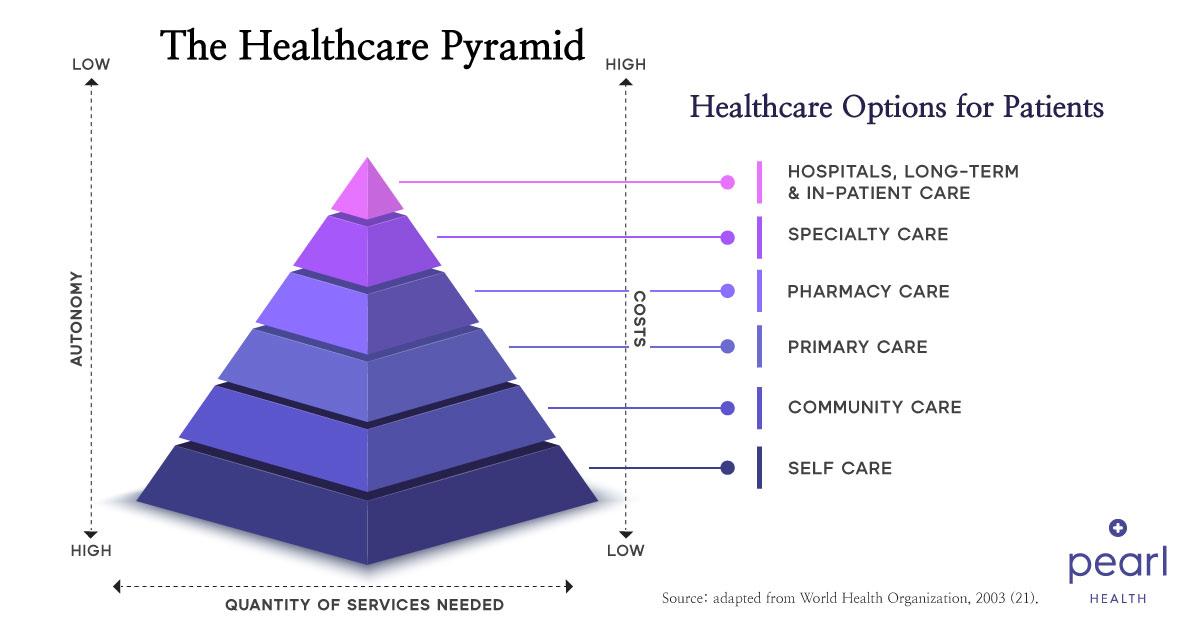

See the adapted graphic below from the World Health Organization. The more we can pull care delivery down the triangle, the more we can obviate the need for unnecessary expense. As patient needs become more acute, we must focus on lower cost, but effective, treatments — especially via primary care.

Source: World Health Organization – https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK544149/figure/ch5.fig3/[/caption]

Source: World Health Organization – https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK544149/figure/ch5.fig3/[/caption]Of course, more complex conditions, as often exhibited in the Medicare population, will require more specialized or intensive utilization. The trickiest part about managing utilization is therefore separating out appropriate utilization from inappropriate utilization.

Optimizing Quality in Healthcare to Drive Value

Consider a provider that, at first glance, seems to deliver a lot of fairly intensive care — that may seem like a bad thing. But that care may be completely appropriate given the cohort of patients that that provider sees. In fact, the same utilization patterns might be appropriate or inappropriate based on the characteristics of the patient panel being managed. Of course, separating out good utilization and bad utilization is inherently intertwined with the second component of the value equation: quality.

‘Quality’ is a bit more nuanced, but at a thematic level, it is generally oriented around:

- Healthcare Outcomes (e.g., did patients get better and did they avoid unnecessary harm?); and

- Patient Satisfaction with — and engagement in — their care.

In upcoming parts of the Value-Based Care playbook, we’ll take a closer look at hypotheses on the leading indicators that contribute to the lagging indicators of healthcare outcomes and patient satisfaction (for more on ‘lagging’ vs. ‘leading’ indicators, read this post). It’s our contention, for the former, that care — both management and delivery — is the primary driver of healthcare outcomes. For the latter, we believe that experience — of both providers and patients — is the primary driver of patient satisfaction and engagement.

Reimagining the Value Equation in Healthcare

Now that we’ve given sufficient definitions to the terms, let’s circle back to the top-level equation. While the equation as written can be theoretically maximized by reducing cost to zero, it’s helpful to think of quality as a side-constraint: the ways in which we reduce costs should not reduce the quality of care provided from the status quo (and should in fact improve quality over time).

Setting aside the evident moral argument for why this should be the case, this actually becomes apparent when you conceive of value-based care as having a mandate to maintain and increase value over time: while lowering costs at the expense of quality may ‘improve value’ in line with the above equation in the immediate term, bad quality (and, as above, therefore bad outcomes, bad processes, and low patient engagement/satisfaction) will lead to a spiral of deteriorating health that will result in high costs down the road.

In summary, we clarify the standard definition of value through the following annotations:

- Cost is ‘unit cost’ multiplied by ‘utilization’.

- ‘Utilization’ may be inappropriate or appropriate based on the clinical circumstances and disease burden of the population being managed. High-value care seeks to minimize inappropriate utilization and maximize appropriate utilization.

- Quality encapsulates ‘healthcare outcomes’, ‘healthcare processes’, and ‘patient satisfaction/engagement’.

- Quality must be maintained or improved; it cannot be reduced.

In Part II, we’ll dive into Pearl’s Playbook for Achieving Value, where we’ll codify some of the key techniques we believe will enable the successful realization of a value-based delivery system in line with these rules.

Interested in following updates to Pearl’s Value-Based Playbook? Follow Pearl Health on LinkedIn or Twitter for regular insights in your newsfeed.