Running a physician practice inevitably means two distinct and often orthogonal challenges: taking care of patients and managing the “business” side of the practice.

A common question we get on the business side of healthcare is whether and how new value-based payment models should play a role. (While there are critical considerations around how these value-based payment models affect patient care, we will put those aside for the purposes of this piece and focus on the business side.)

If we focus on maximizing practice stability and long-term value, we should aim to maximize long term earnings and have those earnings be steady (said differently, we want to minimize earnings volatility).

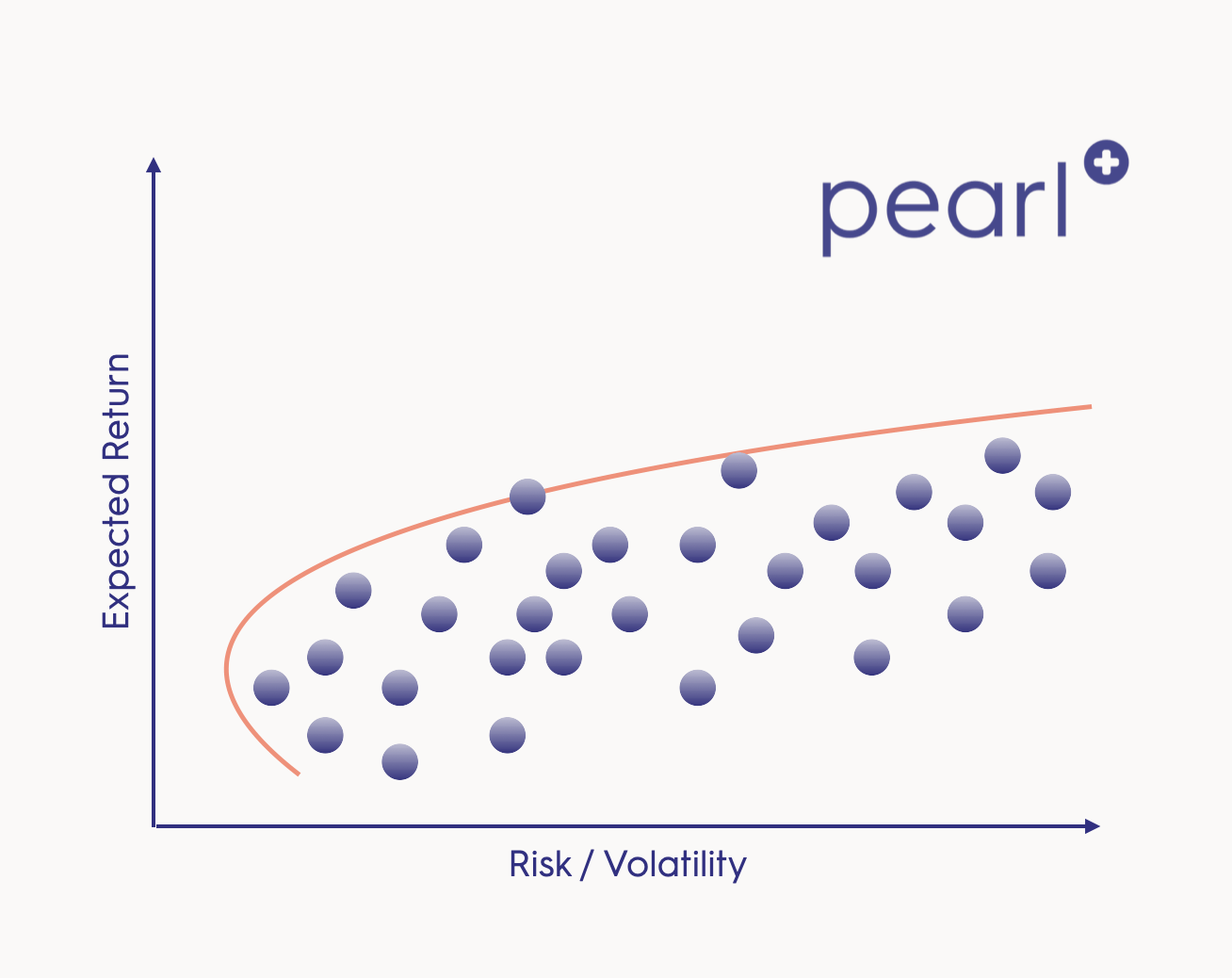

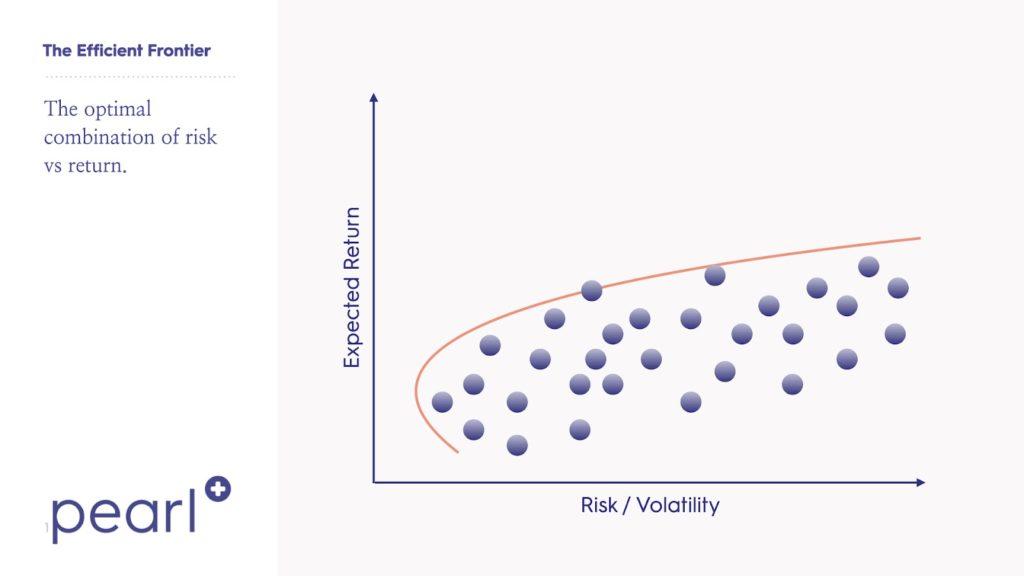

Now, how can we do that? To understand how value based care reimbursement can help with achieving that goal, it’s helpful to borrow some concepts from Modern Portfolio Theory (MPT). In MPT, investors seek an optimal portfolio based on the return streams that they have available to them by considering the expected return, volatility of each and the expected correlation between them. Critically, applying MPT shows us that the return-to-risk ratio of the entire portfolio is usually improved by combining positive expected return streams and taking advantage of the principle of diversification, which minimizes total risk by spreading it out across multiple return streams (“not putting all your eggs in one basket”). Importantly, when we speak of diversification, we refer only to compliant allocations of cohorts of patients to available programs, not ‘cherry picking’ individual patients.

Below, we’ll apply these concepts to the modern physician practice to show the benefits that come from creating a diversified revenue base that is resilient to changes in patient volumes, prices and payer dynamics. We’ll consider traditional fee-for-service, primary care capitation and total cost of care capitation and examine how these can balance each other to achieve an optimal mix of business lines.

Fee for service:

In the traditional fee-for-service model, physicians are reimbursed for each service they perform at a rate negotiated with the payer. Expected earnings are driven by the volume of services performed, the price per service that the practice can command in the market and operating costs.

In a competitive market, upside from this business model is capped: rates can only go so high before payers cut the practice out of their networks and patient volume can only be increased or costs cut so far without compromising quality of care. A great practice can sometimes command higher prices by showing payers that they command loyalty with patients, deliver unique services or that they deliver great quality care; but getting credit for indirect value creation has proven challenging in most fee-for-service arrangements, as outcomes-based compensation is either non-existent or else narrowly defined (e.g. episode/bundle reimbursement).

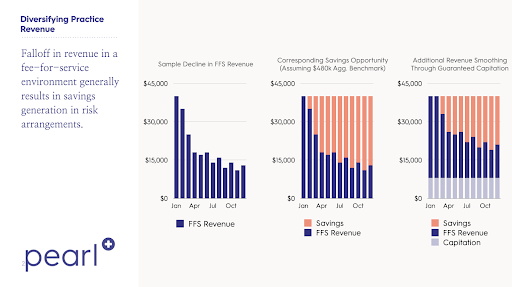

In terms of volatility, the fee for service model is exposed to significant revenue volatility from patient volume, as was made apparent during the covid-19 pandemic. There is also exposure to changes in payer payment policies and changes in operating costs, but patient volume is typically the predominant driver. And with only a small portion of operating costs being truly variable, a big drop in revenues means that a typical practice will quickly find itself losing money.

Primary care [or specialist care] capitation:

In primary care capitation, physician practices negotiate fixed Per Member Per Month (PMPM) reimbursement with the payer in exchange for providing all necessary primary care services to enrolled membership. This rate is typically negotiated in the same manner that FFS rates are negotiated; at the expected average primary care cost, both the payer and provider end up in the same position (putting aside incentives). As a result, because they can be so easily compared to each other, it’s fair to assume the average expected revenues from the two models are similar.

The main advantage of primary care capitation is that it gets rid of short term volatility in patient revenue, smoothing out the primary source of risk to fee-for-service practices. It does leave you with exposure to surges in variable costs (if all of a sudden you provide a lot of visits, it doesn’t come with more revenue), but overall earnings are typically smoother for these practices, which is why the model is gaining popularity in many markets.

Total Cost of Care Risk:

New payment models like Partial or Total Capitation Models have unlocked a totally new business model for physician practices. Under these agreements, physicians receive a PMPM payment to provide care and, at the end of the year, patients’ total cost of care (TCOC) is compared to a benchmark rate to calculate “savings.” Then the practice gets a predetermined portion of the savings. What percentage of savings and whether risk is “two-sided” are both critical terms that will vary across agreements.

What is the expected return of this arrangement? It depends on the terms of the agreement, the practice and the patient population.* But in general, as you would expect, the clearest way to achieve a positive expected return is to control downstream costs. If you can do that, the expected value is almost always positive. Because there is more preventable spend for sicker, older patients, this is often most doable in a Medicare population, which is where risk-based arrangements are most rapidly taking hold.

For a typical primary care practice, TCOC exposure represents a lot of potential upside but also a lot of risk. Of every $100 of medical premiums, the typical fee for service primary care practice is capturing only $4 or $5 in revenues, and running on fairly thin margins (maybe $1). For a patient population of a few thousand patients, it’s very easy for savings versus benchmark to be $3 or $4 in one year and then -$3 or -$4 dollars the next year (for those versed in insurance lingo, you are basically exposed to Medical Loss Ratio volatility). If the practice were on the hook for 100% of savings, this could increase earnings by 4x or put the practice totally out of business. As you increase the size of the patient panel, the predictability of average TCOC goes up and risk goes down.

One important characteristic of TCOC exposure is that it is likely fairly uncorrelated to FFS revenue. In the scenarios where a primary care practice’s FFS revenue falls significantly, risk-based revenues are usually unaffected, if not improved. In the pandemic, when fee for service revenues evaporated across the medical system, overall medical costs fell, so anyone who had exposure to “savings” saw an offsetting increase in savings revenue.

The ideal revenue mix

According to MPT, the ideal portfolio combines positive expected value return streams and harnesses the power of diversification to reduce overall risk. And as has been laid abundantly clear over the last year, this works in healthcare. Practices that had a diversified revenue structure combining fee for service and risk-based revenues had a much more solid financial foundation to weather the pandemic.

The trick is to get the right risk exposure. Practices that swing for the fences and start acting like insurance companies need the capabilities to manage population health and the financial backing to weather a downside scenario. More prudent is to size your risk exposure to what you can comfortably handle, and to analyze the risk arrangements available to you to make sure you can succeed in the agreements you sign. But practices that do this — that thoughtfully take “risk” — can counterintuitively decrease risk and leave themselves better off.

While the value of this diversification is apparent in theory, it is worth noting the operational tension that managing multiple business models introduces. It is difficult to run a physician practice in a way that is optimal for both FFS and capitation, as the former emphasizes visit and patient volume, while the latter is more focused on depressing average per-visit costs and focusing resources on the sicker members of a patient panel. Programs like Direct Contracting allow practices to take risk on a meaningful subset of their patient panel (e.g. their Medicare patients), but do not address other panel components (e.g. commercially insured patients). Pearl strives to help its physician partners not only find the appropriate risk arrangements for them, but also navigate the operational complexities implied by engaging in this multi-model approach, a necessary step in the transition to a value-oriented revenue model.

* You can work with your Pearl advisor to calculate the expected return for various risk arrangements.