There are distinct eras in the development of the modern American healthcare payments system.

- Pre-Insurance Period (Pre-1942): The period prior to World War II involved direct consumer payments for healthcare and limited availability of insurance coverage. There were some capitation solutions and some insurance offerings from business but very limited products and coverage.

- Employer Insurance Period (1942-1965): From that point through 1965, an employer-offered health benefits period emerged, largely because health benefits were excluded from wartime government wage controls.1 Coverage doubled across employees in two decades.

- Government Social Welfare Period (1965-1990): In the mid-1960s, traditional government social welfare programs, distributed in the form of expanded Great Society entitlements, became increasingly prevalent. Medicare and Medicaid led to a lot of coverage and emerging reimbursement models for physicians. By the end of this period most people had some form of health insurance.

- Corporate Healthcare (1990-2013): Starting in the 1990s, with the onset of Medicare Advantage, overlap between corporate healthcare and government social welfare began to emerge and grow in popularity. Public and private partnerships in healthcare, as well as technological innovation, led to a massive healthcare system powered by capitalism and balanced by policy.

- The Great Risk Shift (2013-Present): This article proposes that, beginning around the implementation of the PPACA and followed by the creation of Direct Contracting, the emergence of consumers insuring themselves directly, new risk-bearing entities entering healthcare, provider-led risk models, and maturing capital markets with increased data portability together generated another distinct period, one that we call the Great Risk Shift.

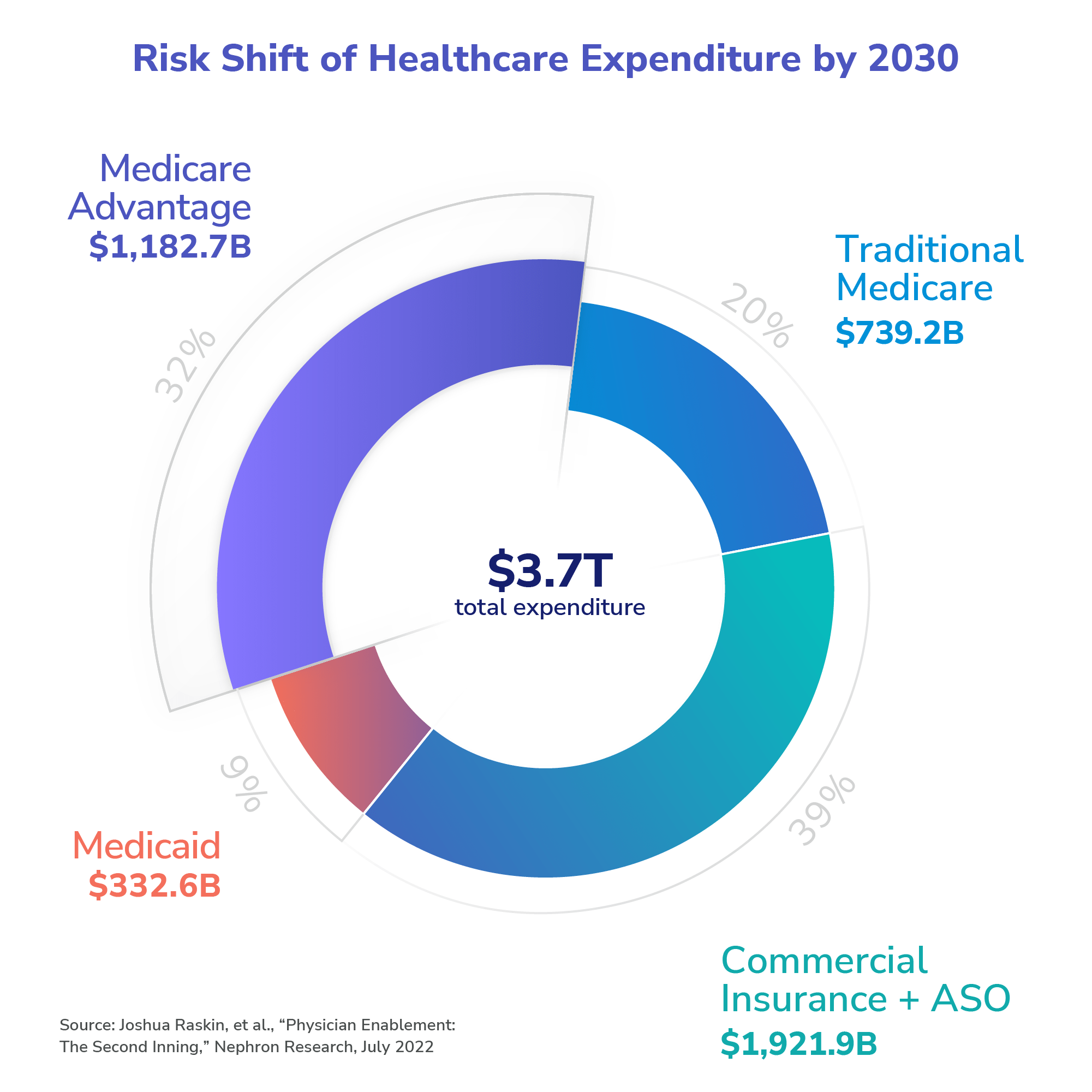

The great risk shift is from entities that traditionally bore healthcare costs — i.e., the government and insurers — to those who have traditionally been the providers and consumers of healthcare — i.e., doctors and patients. This shift involves the transfer of risk related to $4 trillion (and more as time goes on) of healthcare expenditures.2

In some cases it may frustrate those operating in the historical paradigm — i.e., higher co-pays and deductibles or changes in business payment models — while in others, it will create tremendous opportunities for those who understand and appreciate the new era. In particular, the shift may redound to the benefit of over-extended public sector payors, forward-thinking clinical operations, and sophisticated patient groups, provided they avail themselves of emerging data and technological tools that empower them to achieve better outcomes more efficiently.

How did we get here?

Our healthcare system struggles with an agency problem, whereby the person who generates the expense — i.e., either as provider or patient — doesn’t necessarily pay for it. That disconnect, combined with continuous growth in overall expenditures, has created a breakpoint that will inevitably lead to greater rewards for those who can best deliver quality healthcare at lower cost. In other words, our system is moving from one that is largely expense-driven to one that is largely value-driven. Providers are best positioned to enhance the effectiveness and efficiency of care, provided they operate in partnership with those entities that can provide the necessary technological and data tools to make optimal decisions in delivering that care.

Government Policy and Programs

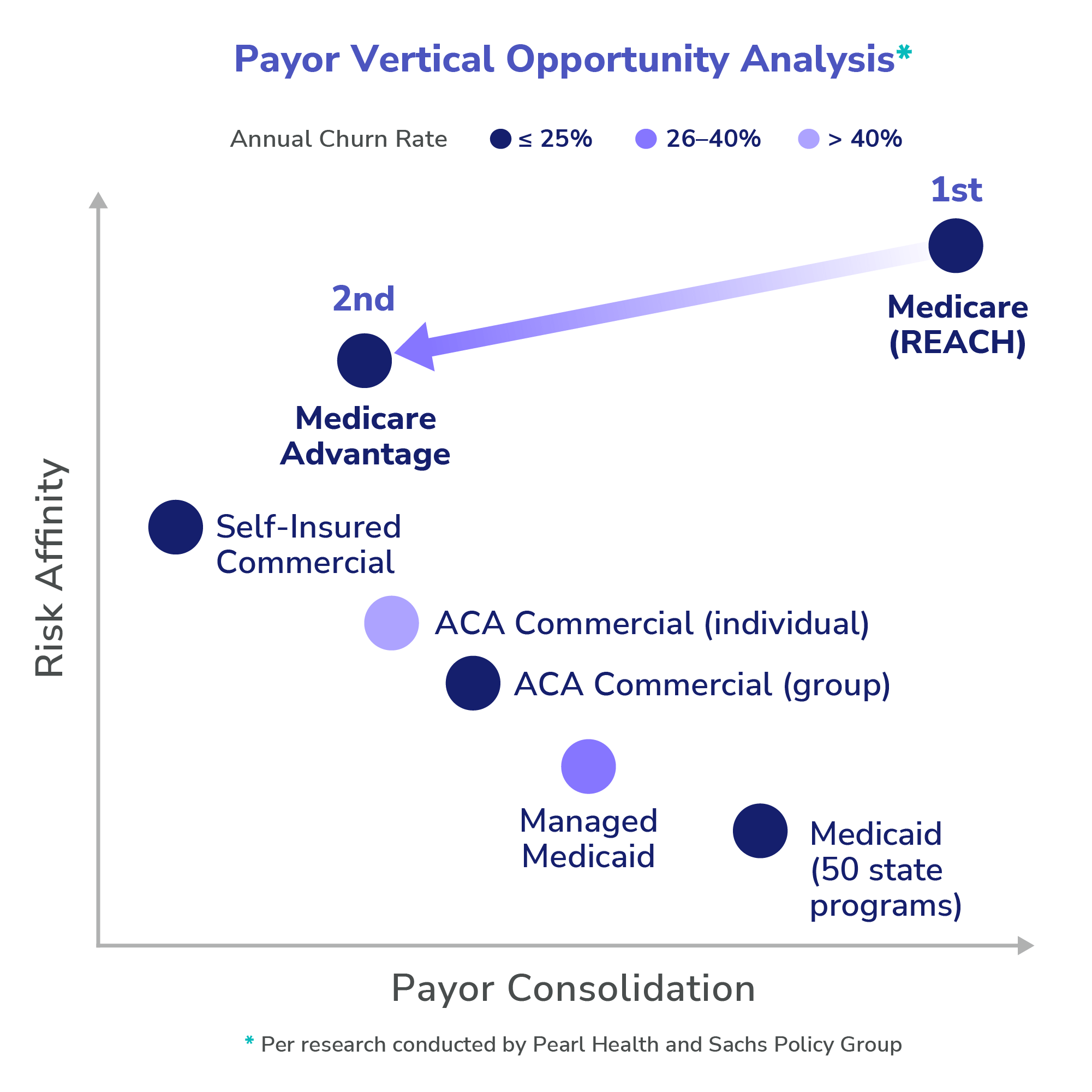

Government programs, like Medicare and Medicaid, are faced with rising costs and a tired tax base with unfavorable demographics. This challenging environment will require payment and pricing innovation. Governments will deploy a variety of techniques to arrest unsustainable cost growth and usher in the great risk shift. An early example is Medicare’s REACH program, preceded by the Medicare Shared Savings Program and a variety of other programs, which creates financial opportunities for physicians and providers who know how to remove waste and increase quality through more holistic management of their patients. Governments will increasingly find ways to pay more to providers who can deliver in these models, and will benefit even further those providers who can amplify their effect by taking advantage of enhanced data sharing and collaboration. These amplified effects — akin to provider super powers — will benefit more than 140 million people who receive government-paid insurance in the form of better, more efficient care.

In REACH, providers have the opportunity, but not the obligation, to assume responsibility for coordinating the care of traditional Medicare members in a full risk arrangement with the government. Over time, models like this will create incentives to deliver efficient, low-cost, and preventative care for seniors and other government program beneficiaries and facilitate more reliable and sustainable budgeting for governments. More importantly, these models will create incentives to ensure that vulnerable beneficiaries do not slip through the cracks that often appear during otherwise non-reimbursable moments. New technologies and data solutions have started to emerge to help providers identify and address key clinical moments in a more holistic patient care regime. Due to the growing availability and interoperability of data models, providers who embrace such solutions will enjoy not only enriched financial opportunities, but also, and most importantly, the care coordination seat at the center of the data flows, which will empower them to address critical health needs when and as needed, rather than serve as subjects of the fee-for-service regime, where procedure codes and insurance company second-guessing reign supreme.

Medicare Advantage: Public-Private Hybrid

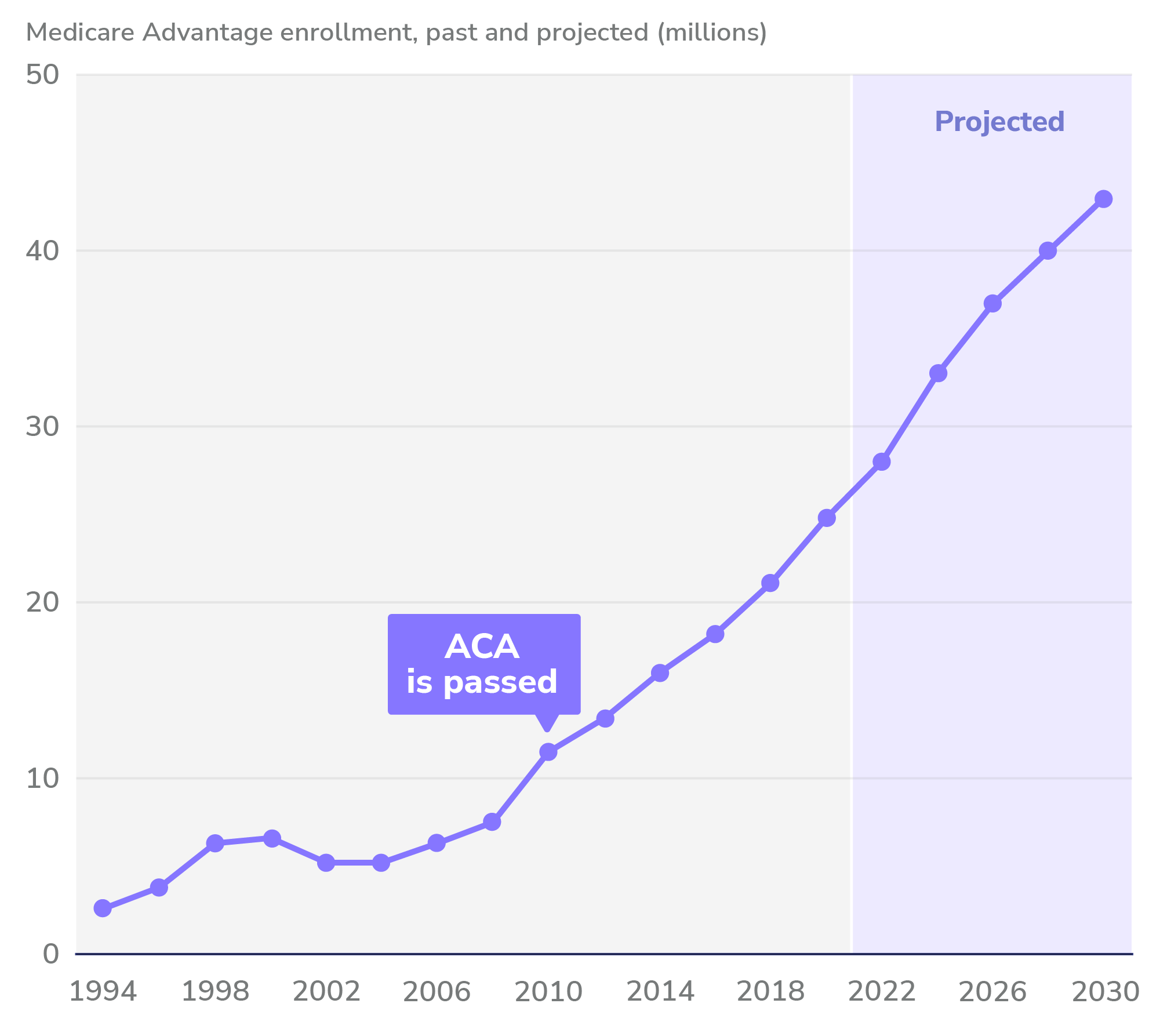

Approximately half of Medicare beneficiaries are in Medicare Advantage plans. The rise of Medicare Advantage is one of the clearest reflections of the contemporary period dominated by corporate healthcare and government social welfare. The government’s partnership with the private sector in Medicare Advantage led to a proliferation of plans and dramatic expansion of enrollment in the program. Larger insurers profited by offering narrower network coverage, managed healthcare, and lower premiums to their clients. The government has largely failed to take advantage of market power in these arrangements, but has derivatively benefited through satisfied beneficiaries who have enjoyed lower out-of-pocket costs and valuable rebates. Medicare Advantage participating insurers are likely to rely more and more on those provider organizations with the ability to quantify costs up front, thereby enabling the insurers to price their plans with more accuracy and manage their risk more effectively. Price plays a huge role in acquisition of Medicare Advantage members, and plans typically only have the blunt instruments of narrow networks and denials to achieve reliability. By contrast, provider-led organizations can help stabilize expenses across panels when they stand to share economics with their insurance plan partners.

Some health plans have tried to stabilize input costs by acquiring practices. This vertical integration is not always welcome news to providers (who have seen their bargaining power decline) and patients (who receive their healthcare from employees of their insurer). Moreover, competition can be stifled, as other health plans see their network strength decline when their providers are acquired by competitors. These acquisitions have led to the creation of so-called “Payvider” entities (provider + payer entities) that better align the financial outcome of health plans with their supply chain costs. This is a powerful opportunity for independent provider organizations to move into the risk management or value-based space without becoming insurance company employees. Providers who become more facile and skilled in cost management, value alignment, and the economics of payors will, irrespective of their personal appetites for cost-sharing arrangements, find themselves in privileged financial positions as compared to their peers who adhere unwaveringly to the thought patterns of the fee-for-service regime.

MA enrollment has grown rapidly in the past decade.

Source: Steven Findlay, Gretchen Jacobson, and Aimee Cicchiello, “Medicare Advantage: A Policy Primer,” explainer, Commonwealth Fund, May 2022.

Commercial (Employer) Insurance

There is less of an incentive to invest in outcomes among commercial payors than the government because people change jobs and the former, over time, cease to be responsible for the health of many of their beneficiaries. In many instances, the benefits of investment in the health of a given beneficiary end up going to benefit the next insurance company that covers that person. This phenomenon requires the “payback curve” for commercial insurers to be shorter, meaning that immediate-term reduction in spend tends to be over-prioritized relative to investments in longer-term patient health. By contrast, governments have a general interest in the health of their people, and the beneficiaries of social welfare are less likely to move on to other forms of coverage, so longer-term investments in the health of beneficiaries in programs like Medicare is sensible.

The growth of clinical models that are virtual and national is a signal that specialized care will be less geographically restricted. Employers may want to benefit their employees by making such salutary care delivery mechanisms available to their workers. In addition to increased convenience for beneficiaries, these mechanisms allow more efficient provider-patient matching, which may make returns on investment in preventive health more efficient and more likely to fall on the correct side of the payback curve. Our delivery system has not, however, yet been able to deploy all the technological tools necessary to take advantage of the value that can be created from well-aligned physicians. As those tools become more pervasive, both at the primary care and specialty levels, they will allow for combination and management of healthcare costs that will result in improvements to patient care and efficiency, much in the same way that vertically-integrated hospital systems have in the historical geographically-bound, fee-for-service regime.

Conclusion

The American healthcare system is a massive, $4+ trillion ecosystem that did not exist 100 years ago and continues to evolve through seismic shifts based on social policy and technological advances. At Pearl Health, we see value-based models as a way to maximize the sustainability of our healthcare system and to align providers with their patients in a way that results in better care and more financial reward flowing to those who coordinate it.

Perhaps most importantly, the power and knowledge that is starting to come from the standardization, processing, and deployment of massive stores of non-interoperable healthcare data can launch providers along the way. We are excited to be the catapult, partnering with providers so that society gets more bang for its healthcare buck by, among other things, moving clinicians into essential care coordination roles, where they can ensure patients get smarter, better healthcare.

- Stephen Mihm, “Employer-based health care was a wartime accident,” Chicago Tribune, February 2017.

- Joshua Raskin, et al., “Physician Enablement Update: The Second Inning, Nephron Research,” July 2022.